Why should our communion with the beloved dead depend on the coincidental turning of the Earth on its axis? Why should we not always be in touch with those who have crossed the threshold, in touch with our own mortality and death? We live in this one world, together with the dead and the long-departed. They are as close to us now as our own skin and bones and blood. This is true, just as it is true that the sky is always full of stars, whether we see them striking out towards us through the darkness of night or lose them awash in the brilliant blues of sun-filled days. Just as it is true that we live embodied, embedded deeply in the seasons and moods of the landscape which lies heavy around us, even as we spin through space on a speck of dust and sea held together by gravity and speed. It is all one world.

— from “The Pulse of Autumn“

In the Druidic tradition that my family and I celebrate, at this time of year we honor our ancestors, the beloved dead — not because they are only available to us during these cooler, darker days when the veil is thin, but because the changes in the land around us awaken us to a keener awareness of grief and loss, as well as reminding us of the joys to be found in the warmth of family, hearth and home.

For the kids, that sense of joy is deep and abiding — I challenge anyone not to crack a smile watching them bounding around among the brightly-colored fallen leaves or splashing through the chilly creek in their rainboots! As they grow older, though, my husband and I have also recognized a growing need to introduce them to the more difficult aspects of this season: coping with pain, sorrow, death and decay — not through the fetishized thrill-seeking of ghost-hunts and horror movies, but with a sense of contemplative reverence and respect.

The grief of the living for the dead is not only the pain of losing loved ones and admired role models to the inevitable passage of time, but also the recognition that the past is, as they say, a foreign country — rife with sorrows and injustices of its own to which we must bear witness. We often find ourselves in an ambivalent relationship with those who came before us. They are as close to us as our own flesh and blood, their choices and mistakes reverberating through time to shape our world and our very sense of self in the present. And yet even so, they often appear to us as strangers, their life experiences sometimes radically different from ours, their thoughts and motivations obscure, perhaps impenetrable. As Druids, we seek to cultivate a relationship with our ancestors that is grounded in understanding and love, but such relationships are challenged by the other-ness of the beloved dead — the intimate strangeness that echoes in our bones, and the once-familiar made strange by the passage of time.

The Problem of Honor

Nowhere is this otherness more obvious than in confronting the legacy of injustice that is our inheritance as white, middle-class Americans. How do we honor ancestors who participated, knowingly or not, in systems of oppression and exploitation, who helped perpetuate injustice against the marginalized and the vulnerable? Do we emphasize only the good that we have inherited, excusing or explaining away the more troubling aspects of the past as “just the way things were back then”? Do we choose instead to turn our backs and walk away, rejecting that part of our history at the risk of forgetting or denying its consequences? Neither choice seems like a real solution to our ambivalence.

There is always pressure to either romanticize or demonize the past. As it recedes into the distance of memory, its complexities are all too easily lost in the mists. The veils of time fall across our vision and we glimpse only vague impressions of a landscape, a culture, a handful of faces on the edge of our perception that seem to change and fade when we turn to look again. What does it mean to part this veil, to honor the ancestors? In her book, Living With Honour, Druidic writer Emma Restall Orr notes that ideas of honor and integrity are inextricably bound up with the idea of coming face-to-face with another — with the Other — whether family member or stranger, friend or foe. This face-to-face encounter requires us to respect the unique individuality of the other, to resist the urge to simplify or reduce them to a projection of our own minds, while at the same time recognizing in the face of the stranger the web of interconnection that binds us together and shapes us both through mutual relationship. To have honor is to face up to your ethical responsibilities here and now, to accept your ability to respond with integrity and love even in situations you did not necessarily help create. To live in honorable relationship is to look the other in the eye, to acknowledge the full and unique personhood of the one facing you, whether across the dinner table or the battlefield, or across the misty distance of centuries.

At this time of year, we strive to honor the beloved dead in this way — to draw aside the veils of time and come face-to-face with our history in all its complexity, even while acknowledging and accepting the distance that inevitably separates us from the past.

Crafting Ancestor Prayer Beads

This year, our Samhain celebration with the kids took the form of a “teaching ritual” introducing them to the ancestors through a bit of informal bead-and-knot folk magic. After a week of exploring our family history and the history of our country — visiting places like the battlefields of Gettysburg and the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian — we led the kids in a craft project to create a prayer bead bracelet representing their connection to the beloved dead and their own place in the on-going cycles of life and death.

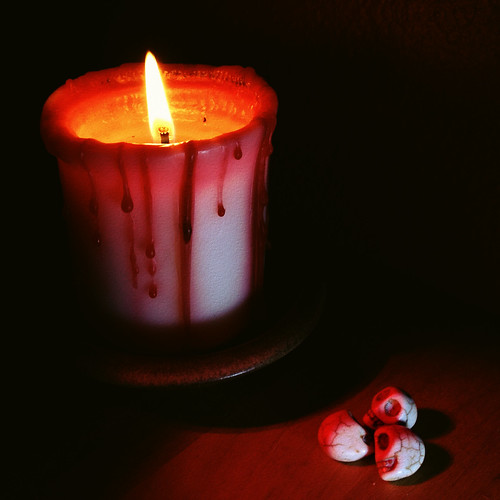

The ancient Celts were particularly attuned to the power of the face and the head, and their myths are full of severed heads that continued to talk even after death, providing power, protection and prophecies to those who would listen. For our craft, we chose stone beads carved into the shape of a skull to symbolize the wisdom and blessings of an honorable, face-to-face relationship with the beloved dead. The beads were in three colors also sacred in Celtic tradition — red, black and white — to represent the three types of ancestors that we honor: Ancestors of Blood, Land and Spirit. As we passed the beads around the circle in the warm glow of flickering candles, each of us contemplated what gifts and responsibilities we have inherited from our ancestors as I shared these thoughts aloud:

The Ancestors of Blood are all those relatives who have come before us and passed on: grandparents, great-grandparents, great aunts and uncles, and many more. These are the beloved dead who are tied to us genetically — “by blood” — all those who have passed on their inheritance through our DNA, but also through family stories and traditions, daily habits and ways of living. Like our family members still living today, our ancestors weren’t always perfect and they didn’t always get along. From them, we inherit many wonderful blessings, but we must also acknowledge that we are still living with some of their mistakes. Whether we agree with their choices or not, the way they lived has had a deep and lasting impact on who we are today, just as our choices will shape the future of those who come after us. Honoring our ancestors of blood means recognizing this interconnection of past and future, and accepting the full and complex humanity within ourselves, our kin and others. Just as we benefit from the hard work and blessings of those who came before us, so too do we bear the responsibility to learn from their mistakes and work to make the world a better place for future generations.

The Ancestors of Spirit are those beloved dead who have helped to shape the human community and culture that we are a part of, as well as historical figures and role models who came from other cultures besides our own and have influenced our view of the world in important ways. These ancestors may not be related to us physically, but through their impact on the wider society they have helped to shape the spiritual path that we walk by the examples that they set and the traditions they have established and passed down to us. They are our mentors and guides in spirit and inspiration. As with the ancestors of blood, we must strive to remember that our ancestors of spirit were human beings, just like us, who lived complex and diverse lives. The insights they discovered and traditions they’ve created can provide us with guidance along our journey, but in the end our journey is always our own, the ancestors cannot walk the path for us. Honoring our ancestors of spirit means following the examples they set for us, not only by appreciating with gratitude the traditions they have passed down but also having the courage to forge new traditions and create new paths forward when old ways of living no longer serve.

Finally, the Ancestors of the Land are all those who have lived on the land before us and shaped it for generations, shaping us in turn as we participate in the more-than-human community of the natural world. These are the beloved dead who once lived on the land where we were born, as well as those who lived on the land where we now live today. Here in America, the ancestors of the land include not only European settlers who established towns and cities and transformed forests into farmland, but also the indigenous peoples who have lived with and shaped the landscape for thousands of years. (We can even include the plants and animals who dwell in the woodlands, rivers, mountains and meadows that are all around us, for they too are our kin and they have left their own unique marks on the land.) As we move from place to place throughout our lives, we are always entering into new communities with their own unique histories and ways of living. The ancestors of each landscape have their own lessons to teach, their own blessings to share, and their own struggles that need to be respected and understood. Honoring the ancestors of the land means understanding that we are guests of the place in which we live, not its owners or masters, and that we must strive to be hospitable and responsible hosts for future generations in our turn.

When everyone had selected their beads (four beads of each color, representing the powers of earth, air, fire and water within each) and had strung them onto the cord that bound them all together in a circle rooted in understanding and belonging, we each chose one last bead — to represent ourselves and our place in the circle — and then knotted the cord three times, and then thrice again with these words:

I honor the ancestors who came before me.

By earth, sky and sea, I honor them.I take my place in the circle of life and death.

I honor the descendants who will come after me.

By earth, sky and sea, I honor them.With this knot, I complete the circle.

So may it be.

May this season of death and darkness bring you the rich peace of the earth and all who sleep in her embrace.

Update: A bunch of you have asked for more details on how to make the prayer beads mentioned in this post, so I put together a handy-dandy step-by-step tutorial. You can check it out here!

Update: A bunch of you have asked for more details on how to make the prayer beads mentioned in this post, so I put together a handy-dandy step-by-step tutorial. You can check it out here!

So profound

LikeLike